Watch out Spider-Man: The real world is one step closer to creating spider glue.

Researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, UMBC, have deciphered the complete sequences of two genes, which allow spiders to create the sticky stuff that keeps prey trapped in webs.

The research, considered a world-first, is published in the June 1 issue of Genes, Genomes, Genetics.

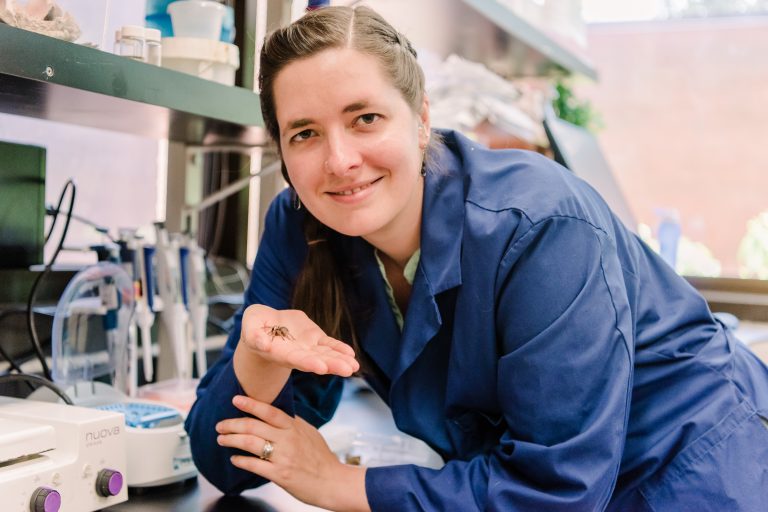

Report co-authors UMBC postdoctoral fellow Sarah Stellwagen and Rebecca Renberg of the Army Research Lab spent two years completing the incredibly complicated sequences.

The findings could help other scientists sequence more silk and glue genes, and hopefully, lead to some giant leaps in the field of biomaterials.

Spider silk, which is both incredibly flexible and strong, is considered the “next big thing in biomaterials,” according to UMBC.

But while spiders convert liquid silk into solids inside their bodies to make their webs, humans haven’t been able to replicate the process in a large industrial scale, according to Stellwagen.

But spider glue remains a liquid inside the body of the spider and outside on the web.

And that has “great potential” in organic pest control, according to UMBC.

Farmers could one day spray it along a barn wall to keep insects away from their livestock or pests far from crops. It could even be used to cut down on mosquito-born illnesses.

“This stuff evolved to capture insect prey,” Stellwagen said in a statement.

For now, the researchers are passing the torch to the next Peter Parker willing to take up the challenge.

“I’m super excited that I was able to finally figure out the puzzle, because it was just so hard,” Stellwagen added. While it was a much bigger challenge than she expected, “Ultimately we learned a lot, and I am happy to put that out there for the next person who is trying to solve some ridiculous gene.”

Fittingly, the newest Spider-Man film — Spider-Man: Far From Home — comes out next month.

Photos Marlayna Demond /UMBC